by Sarah Tanguy

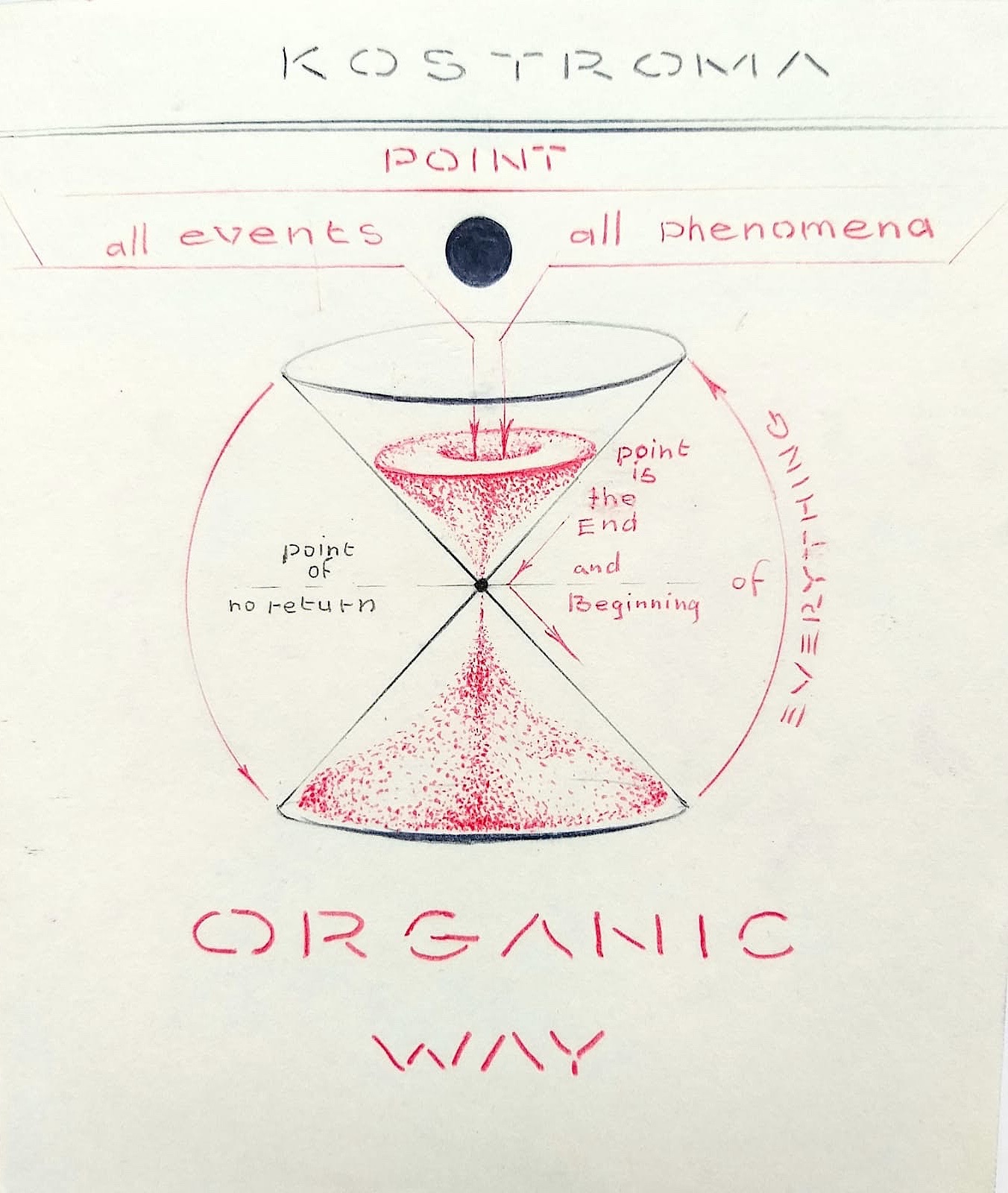

Alexei Kostroma seeks to place his work in an organic, all-encompassing context: “Nature and creative work have a common function of reproduction based on birth and death, self-organization and self-development. Thus creative development, so apparently similar to organic development, was what forced me to examine the interaction of organic and artistic processes.” – from the Kostroma’s diary, 1995

Ducking to avoid water-filled yellow balloons, the viewer enters one of the many rooms at Gallery Navicula Artis, a labyrinthine alternative space on old St. Petersburg. The occasion is Alexei Kostroma’s installation, Inventorying Yellow Rain. Instantly, the eye spies, in the center, a large, glowing, open cube made of yellow balloons, then takes in the paintings speckled with yellow powder pigment on the walls. What could possibly explain such a seemingly odd grouping of works?

Since 1990, Kostroma has dreamt of inventorying rain: “Millions of falling drops cut the city air space with thin strings and spellbind me.”1 It wasn’t until the summer of 1998, when St. Petersburg experienced especially heavy rainfall, that he achieved his goal. With obsessive persistence, he sought to capture rain, to measure it, to understand its trajectory and its retention of shape (which he subsequently learned was due to its magnetic charge). He chose the color yellow, not for its association with pollution but as an optimistic cure for the grayness of rain. A year later, his research culminated in Inventorying Yellow Rain.

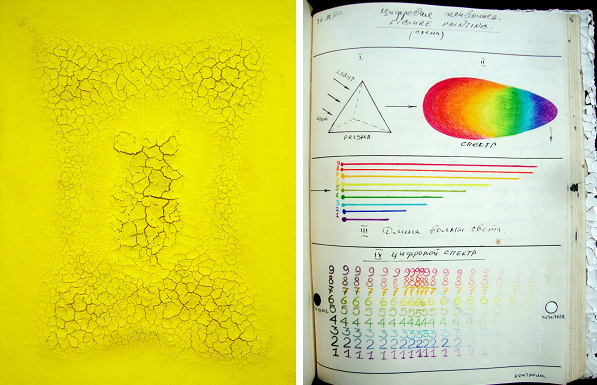

An abiding tenet of Kostroma’s practice, “inventorying is an artistic action in which an object with a clear structure is covered with a sequence of numbers from 1 to 9. The resulting number is the inventory number of this object.”2

The artist got the idea in 1990 after a chance encounter at the Museum of Local History and Economy in a small village in northern Germany. He noticed a petrified little mound that was inscribed with an inventory number. A nearby label identified it as a 14th-century sample of cow dung, which proved the existence of agriculture and wealth in Germany at that time. After this incident, Kostroma became fascinated by inventory numbers. Some of his early projects in 1992 involved inventorying various configurations of stones and trash.

Kostroma wanted to see how rain fits into more inclusive systems and interacts with gravitational and magnetic forces. Not being a scientist himself and only remembering bits of information he had learned in school, he approached Tamara Alexandrovna Pershina, a physicist at the Main Geophysical Observatory in St. Petersburg, who has studied and photographed micro drops of rain for the last several decades. With the help of her work, Kostroma noted a similarity between rain patterns and those formed by the Milky Way and reached certain understandings. Rain is essential for life. Linking heaven and earth, it bears cosmic data and offers a key to understanding the structure of the universe: “Rain is omnipresent. Cows are covered by rain… City is covered by rain… Passions are covered by rain. Dreams are covered by rain…’ In particular, he was drawn to the spiral movement of rain streams. ‘Drops are distributed on the plane along arches, in layers, and form segments of circles with a radius from 15 to 50 mm”.4

How to measure rain volumetrically proved to be a great challenge. Scientists have used buckets. Kostroma’s solution was to create a one-meter cube of yellow children’s balloons and to fill the balloons with a ton of water. The effect of this giant ‘raindrop’ box was mesmerizing. The animal and cartoon faces stenciled on the balloons lent a festive quality, recalling water bombs that the artist admits throwing at innocent passerby in his childhood. The balloons themselves appeared weightless, even buoyant. Their overlapping transparency created a kaleidoscope of reflections and optical distortions. Air bubbles and blemish-like, darker yellow spots around the balloons’ mouthpieces acted as complicating variables whose formations indicated their being changing microcosms.

The ingenious painting technique Kostroma developed to inventory rain loosely combines aspects of pointillism, Abstract Expressionism, and process art. First, he placed a white gessoed canvas outside his studio window for seven seconds. Once the canvas was inside again, he applied yellow pigment powder to its surface and inverted it. When he turned it back, the pigment remained only where the canvas was wet and created shapes which reflected the intensity (ranging from mists to typhoon) and the pattern of a particular rainfall. The final stage involved gluing the pigment in place with a syringe and numbering the drops in fuchsia ink. With this approach, he created abstract paintings as well as pictographic works. While a precedent exists in Yves Klein’s rain paintings, Klein was more interested in texture, while Kostroma wants to unravel underlying physical processes.

This interest in systems characterizes Kostroma’s 10-year career, as he seeks to place his work in an organic, all-encompassing context: “Nature and creative work have a common function of reproduction based on birth and death, self-organization and self-development. Thus creative development, so apparently similar to organic development, was what forced me to examine the interaction of organic and artistic processes.”5

While organic ideology in Russia shaped much of late 19-th century philosophy and religion and informed select artistic practice at the start of the 20th century, it gained currency in the 1990s.6 Many artists, including Kostroma, regard this belief system as a vital and dynamic replacement for postindustrial and post-Soviet rhetoric.

Kostroma studied painting at the Repin Institute of Painting and Architecture in St. Petersburg. After graduating in 1989, he increasingly felt the need for more relief in his works. He began making sculptures and installations, which often included collaboration and performances. In 1991, along with his partner Nadja Bukreeva, he founded TUT-I-TAM (‘Here and There’). The mission of this loose and ideologically independent artist group was and continues to be producing exhibitions and urban projects in St. Petersburg. For many of these, Kostroma uses aspects of his home city as inspiration, from its monuments and holidays to its weather. He prefers minimal shapes and ephemeral or fragile materials, including eggshells, feathers, and balloons. The idea of play and games tempers Kostroma’s goal of bringing art to public.

Early on Kostroma adopted the egg and the feather as personal hieroglyphs for his projects – only white feathers, as he is quick to point out, which he gets in bulk from local chicken farms. He sees the feather as an ancient sign, not as decoration. It represents the ideal way of life and stands out for its softness and its lack of aggression. In Russia, as in many other parts of the world, the word itself is associated with numerous expressions and states. A feather bed, Alexander Borovsky notes, is linked to “laziness, a feature of national character,” and as a verb, it means “to be fledged.”7

In addition to inventorying, “introspective action” represents another cornerstone of Kostroma’s practice. “Introspective action demands self-analysis, self-observation during any prepared action. This is the thought-out illustration of an idea including moments of improvisation where the spectator is clearly provoked to think.”8

An early manifestation was Free Russia, in 1991. That was the first year that November 7 was celebrated not as the Day of the Great October Revolution but as the “Day of Pluralism.” With the support of the St. Petersburg Commodity and Stock Exchange and local authorities, Tut-I-Tam erected Alexander’s Column II the following day on the Palace Square. Made out of 2,500 children’s balloons of different colors, the colossal sculpture broke free from its tether and rose to the heavens with the crowds cheering on.

In X-Rays of the Black Square (1992), Kostroma takes on one of the great icons of 20-th century art. Certainly Malevich’s work is an ongoing source of inspiration and a foil for Russian artists. Kostroma created a five-meter square of 900 condoms, filled with water and lit from the inside, to represent the negative of Malevich’s square as well as its molecular structure. A plastic sheath, in the form of a cube and emitting the sound of the artist’s breathing, encapsulated the condoms. An X-ray was then taken of the giant incubation. Two days later, the condoms burst from light exposure, leaving a large black pool. As writer Mikhail Kuzmin commented: “At some point in the future when an objective history of art will be written, the birth of Malevich’s Black Square and its “death” at the hands of Alexei Kostroma will be considered as integral parts of the same process.”9

Another landmark project is Communicational Information Egg and the Fat Hen (1992-93). An eight-meter-high hen, made from lightweight fabric and activated by two internal ventilators, greeted curious visitors to the Central Exhibition Hall of St. Petersburg’s Manezh. Side windows revealed a large egg on the inside, which bore a video screen and, unbeknownst to the audience, held the artist. During the performance, the hen gave birth to the egg. Sprouting red legs, the egg immediately began running about and emitting the voices of three TV channels. The piece’s subject matter, which combined the cosmic egg of life with a contemporary form of communication, suggested a model of universal harmony. A year later, Evolution of Egg addressed the process of absorption wherein substitutions of images flowed freely from the egg as the perfect shape, to a rooster, to the head of Christ inscribed in a circle from the Novgorod Mandylion, a 12-th century icon that reproduces a miraculous impression of Christ’s features on a cloth.

Like Christo’s wrapping, Kostroma’s feathering is essentially a transformative act performed on a static object. In Kostroma’s case, feathering reestablishes the bond between culture and nature: “It immediately masters the space in which it ends up by chance – either due to fate or due to the artist’s will… The FEATHERING PROCESS does not demand from the artist that titanic effort connected with the implementation of each mad project, but rather turns the surrounding events into an object for silent contemplation.”10

Since the early ‘90s, Kostroma has feathered various objects, including a black cube, an image of the Mona Lisa, and a cannon from the Peter and Paul Fortress in St. Petersburg. In the latter, the feathered cannon fired a ball whose egg-like shape became a bird in flight. This pacifist metamorphosis even made it into Guinness Book of World Records. Feathering the Volga (the Volga was the luxury car of Soviet party elite) was another instance of exchanging the existing aura of a cultural artifact for a new, nontraditional one.

Kostroma also “intuitively gravitated” toward the spiral, to use his own words. Its coil shape implies progression. It manifests how macro and microcosmic relationships reflect each other. It protects and preserves life, both in nature and society. Over the years, he has explored its occurrence in hair braids, in ferns and other plants, in the protein spirals of the egg white which anchors the yolk, in sea and snail shells, in DNA, in the Milky Way, and most recently, in rain. In contemporary art, Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty comes to mind as a landmark example, and in science, Professor E.N.Sinskaya conceived the law of spiral evolution in 1948.11

Kostroma’s interest in spirals and feathers come together in Penguin Spiral. First shown in 1998 in Kirchheim, Germany, the large-scale installation was on view at the State Russian Museum in St. Petersburg in the spring of 1999. The project’s genesis stemmed from an article in a science magazine about the living double helix that groups of 200 to 300 penguins (feathered organisms, the artist notes) maintain to stay alive in critical conditions. Inside the helix temperatures hover at plus 10 degrees centigrade, in contrast to outside readings of minus 50. Kostroma re-created such a pathway, forcing viewers to form a queue and join the spiral of “social heating.”12

The installation featured a giant spiral, which was lit internally and composed of some 50 kilos of feathers. An inverted, truncated pyramid occupied the center. Its feathered cupola became a symbol of the womb, with the phrase “Mysterium Magnum” emerging from the glow of black light. A side wall displayed a series of feathered panels, with such themes as life/ death, entrance/exit, and egg/eye. At the far end of the space, a video projection, using new age music, combined images Kostroma made of various spirals such as smoke and water with some of royal penguins taken from a documentary. Although his interest in animals relates him to contemporaries like Damien Hirst, Kostroma’s work is both a social critique and a positive discourse on the ecosystem.

Restless in his studio, Kostroma himself seems to operate in a spiral, as he details his ambitious plans to reach larger audiences. Spirals, feathers, and other reminders of previous works contrast with giant, primary-colored and primary-shaped sculptures earmarked for an upcoming performance in Cologne titled Organic Presentation: Subjectless World of Nature in Russian Avant-Garde. From the room’s organized chaos, one notes a strong bond between his early performances and objects, which recall Claes Oldenburg’s Happenings, and this new performance work. The point of departure for this performance, he explains, is Play with no Subject, written and performed by Russian avant-garde artist Mikhail Matyushin in 1922-23. While in general Kostroma’s works tend to be festive, he points out that “What I do is an artistic project, not a party meeting or ‘happiness propaganda.’ ”13 Beyond their grounding in the everyday and their broad appeal, his works seek to uncover underlying patterns and suggest a manifesto for a new world order.

© Sarah Tanguy is a writer and curator based in Washington, DC.

SCULPTURE, July/August 2000, Vol. 19 No. 6, Washington, DC , USA

1 Diary entry, August 27, 1999.2 Catalog of Exhibitions and Projects of Tut-I-Tam, 1991-1996 (St. Petersburg, 1997), p.31.

3 Diary entry, September 15, 1998.

4 Inventorying Yellow Rain (St. Petersburg, 1999), exhibition catalog, p.13.

5 Diary entry, December 24, 1995.

6 N.O. Lossky, World as Organic Whole, pp.350-51, cited in Inventorying Yellow Rain, op.cit., p.13.

7 Alexander Borovsky, “Kostroma’s Penguin Caravan Goes Through Hummocks” in Penguin Spiral (St. Petersburg, 1999), exhibition catalogue, p.22.

8 Catalog of Exhibitions and Projects of Tut-I-Tam, op. cit., p.36.

9 Ibid., p.37.

10 Diary entry, June 29, 1994.